When the Union Cabinet cleared the One Nation One Election (ONOE) plan, it instantly generated a national debate. The concept is ambitious—aligning Lok Sabha, state assembly, and even local body elections into a single gigantic electoral exercise. The government says it will save money, enhance governance, and ensure stability, but others worry that it may undermine federalism and upset democratic processes.

I am caught in the middle of this debate—thrilled at the prospect of efficiency but also apprehensive about the pitfalls it entails. The question is, can India’s complex and pluralistic democracy cope with such a radical change? Or are we unleashing a constitutional Pandora’s box?

A Blast from the Past: When Elections Were in Sync

It may astound many that One Nation One Election(ONOE) is not a new idea. During the early part of independent India, between 1951 and 1967, elections to Lok Sabha and state assemblies were simultaneous. It was a clean, orderly system that helped in smoother governance.

But this system began to break in 1968-69, when state governments also began disintegrating as a result of defections and dismissals. In 1970, the Lok Sabha itself was preemptively dissolved, and thereafter elections became intermittent.

Since then, India has been in a continuous election cycle—one state or another is voting continuously. Some states such as Odisha and Andhra Pradesh continue to conduct their assembly elections simultaneously with the Lok Sabha polls, but for the majority of states, elections are conducted at different times.

The Ram Nath Kovind Committee, which examined One Nation One Election, sees it as a return to those early, simpler times. But can a modern, politically diverse India go back to that system? That’s the big question.

Modi’s Big Push: The Political Will Behind ONOE

The idea of ONOE gained momentum when Prime Minister Narendra Modi started advocating for it in 2017. He argued that frequent elections drain the country’s resources and disrupt governance.

In 2024, the Kovind Committee report had suggested an organized plan:

- Synchronize Lok Sabha and state assembly polls first.

- Phase-in local body elections within 100 days of the national elections.

This plan also sounds organized, but the mammoth challenge persists: How do you make 28 states, 8 Union Territories, and a billion voters adhere to a common schedule?

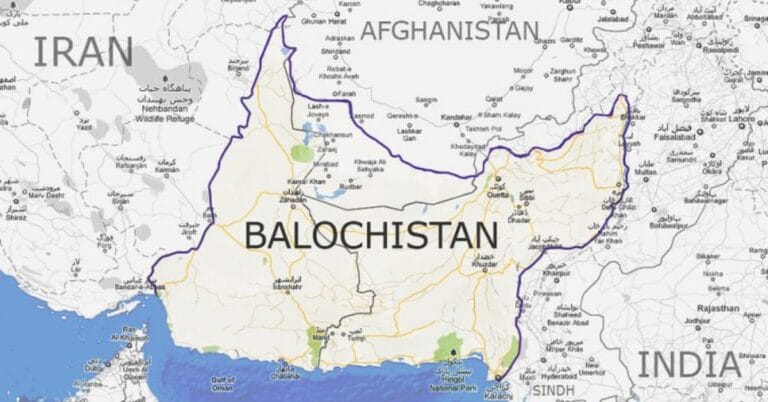

Also read: Balochistan: A Land of Riches, Betrayal and Resistance

The Upside: Why It Might Just Work

Saving Money and Resources

Elections cost money. The 2019 Lok Sabha elections themselves cost approximately ₹60,000 crore, ranging from security arrangements to publicity campaigns to make people aware of the elections.

With ONOE, we could significantly reduce election costs. Consider fewer polling booths, reduced deployment of security personnel, and less electoral logistics expense. The Kovind Committee believes we could save thousands of crores in the long run.

Others claim that these savings are overstated, but no one can deny that holding elections together would cut down on the cost.

Reduced Governance Disruption

Election season brings with it the Model Code of Conduct (MCC), which puts a stop to new policy initiatives and government schemes. Currently, with elections being conducted somewhere nearly every couple of months, governance is interrupted all the time.

With One Nation One Election, the MCC would be applied once every five years. This would enable policymakers and bureaucrats to concentrate on long-term governance rather than being in election mode all the time.

I have witnessed with my own eyes how elections hold back development projects. With each announcement of an election, everything comes to a halt—no new roads, no significant policy initiatives. One synchronized election could liberate governments from having to think about governance only as a means of winning votes.

Politicians Operating on Short-Term Thinking

Repeated elections make politicians stay in campaign mode continuously. All their choices are governed by short-term electoral arithmetic, resulting in populist actions instead of long-term policy decisions.

A political science student friend once told me, “If politicians didn’t fear facing another election every year, they might focus on governing and not short-term promises.” Fair enough.

If leaders had five full years with no fear of losing votes at the next state election, then they might promote long-term vision and improved governance.

Increased Voter Turnout and Awareness

Election fatigue is a thing. By the third or fourth round of elections, voter passion declines.

67% of voters turned out in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, but most state elections barely reach 60%. By lumping all elections together, One Nation One Election may get more people to vote—people will treat it as a one-time, high-stakes affair instead of just another routine vote.

Additionally, voters will have to think about both national and state issues at the same time, which could lead to more informed voting decisions.

The Flip Side: Challenges and Constitutional Hurdles

Major Constitutional Changes Needed

One Nation One Election isn’t just a logistical challenge—it’s a legal one. We’d have to amend at least six constitutional provisions (including Articles 83, 172, 85, and 356) that define the terms of governments.

A few states will be forced to abbreviate short or lengthen their terms to fit the One Nation One Election schedule. Is that reasonable to voters who voted for a five-year government? This is where democratic ethics set in.

Risk to Federalism

A serious concern is that One Nation One Election will dilute regional concerns. If national and state elections are coincidental, will voters think only of national parties and neglect regional concerns?

For instance, in 2019, the national BJP campaign dominated regional parties such as the Telugu Desam Party in Andhra Pradesh. If this occurs throughout India, regional voices could be drowned out.

India is a federal democracy, so both the Centre and states require autonomy. One election could centralize power too much, which would undermine the diversity of regional politics.

What If a Government Falls During Mid-Term?

One of the most challenging questions: What if a government collapses before the end of its five-year term?

The Kovind Report presents two possible answers:

- President’s Rule till the next synchronized election.

- A new election, upsetting the whole system.

Neither is very satisfactory. President’s Rule may be abused to retain a state under Central rule, while fresh elections negate the purpose of ONOE.

This is a huge constitutional and practical challenge that has not been adequately addressed so far.

Where We Stand Now

The government is enthusiastic about One Nation One Election, but the passage of the necessary constitutional amendments requires a two-thirds majority in Parliament, along with half the states’ approval. Opposition parties and regional governments are unconvinced.

The Kovind Committee has given a plan of implementation by 2029, but huge challenges lie ahead—political, constitutional, and logistical.

Final Thoughts: Is One Nation One Election Worth It?

I understand the attraction of One Nation One Election—it’s budget-friendly, enhances governance, and might make politics more policy-oriented. But obstacles are massive—from legal hurdles to issues of federalism.

A likely middle ground? Begin small—sync elections in some states first, test the waters, and then scale up.

If done right, One Nation One Election could make Indian democracy more efficient and stable. But rushing into it without safeguards could do more harm than good.

What do you think—a revolutionary reform or a risky gamble?

Join us on Twitter, Linkedin, Instagram, Facebook, Whatsapp.

About the Author: Karthik Tyagi

JRF, Political Science | Columnist | Writer

Karthik Tyagi is a political analyst specializing in geopolitics, governance, and international affairs. As a JRF in Political Science, he contributes to political journals and newspapers, offering sharp insights into global and national issues.