Re-strategising the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project

Securing India’s Connectivity to the Bay of BengalOne of India’s Act East Policy linchpins, the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP), remains strategically fragile due to two critical geopolitical constraints: first, the protracted civil war and political instability in Myanmar, and second, India’s complex bilateral relations with Bangladesh.

This brief examines the implications of regional volatility for the KMTTP and finds that India may need to move beyond traditional state-centric bilateral dependencies to secure its strategic interests. India could take steps to reduce operational risks in the KMTTP corridor by engaging relevant local and non-state actors in Myanmar and focusing on asset preservation in the India–Bangladesh corridor.

India can also attempt to embed its projects within multilateral platforms such as BIMSTEC while also exploring alternative routes to secure connectivity to the Bay of Bengal independently of its immediate land borders.

Introduction

Connectivity, including economic links, social and cultural ties, and infrastructure, is one of the cornerstones of 21st-century statecraft1. For India, infrastructure connectivity plays an important role in strengthening its strategic periphery, particularly the Bay of Bengal region and the historically isolated Northeastern region. One such initiative of India is the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP), which aims to enhance connectivity between India and Myanmar, as well as between rest of India and the Northeastern states.

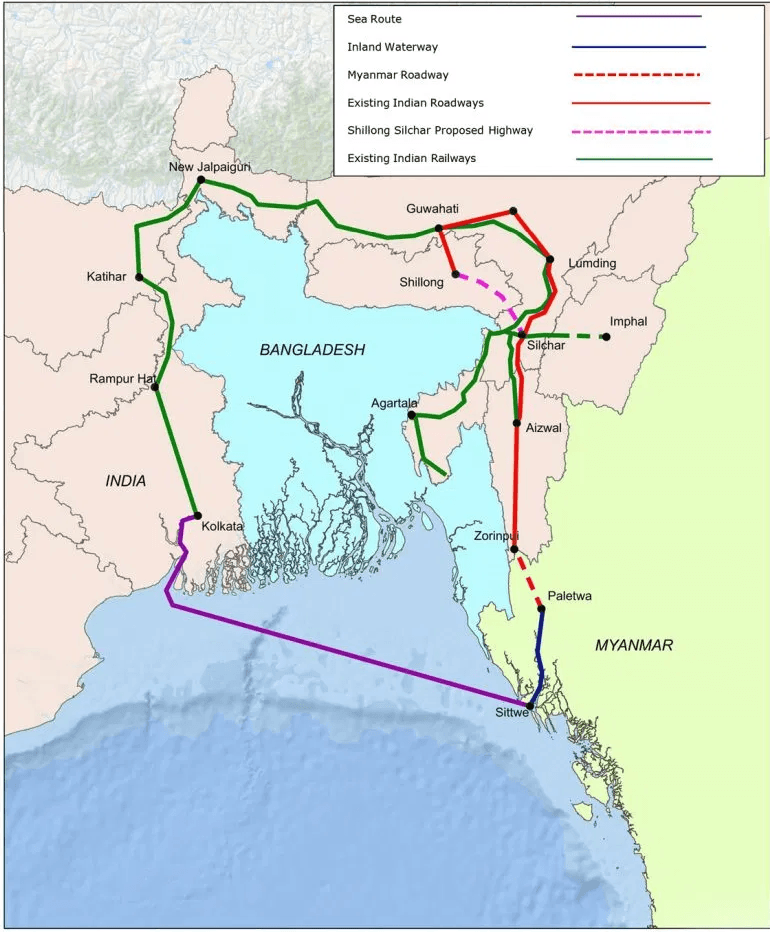

The KMTTP was initiated in 2008 primarily as a response to India’s geographic vulnerability arising from the Siliguri Corridor, which is a narrow landlocked tract serving as the only terrestrial link between the Northeast Indian region and the rest of India2. This project aimed to establish a 900 km multi-modal route, integrating sea, riverine, and road transport. The project has two core transit components: a waterway linking Kolkata in India to Sittwe in Myanmar, traversing the Kaladan River to Paletwa, and a road link from Paletwa to Zorinpui in Mizoram.

While the Sittwe port is ready for operations, the road connectivity is still underway. Once the latter is operational, it will reduce the distance between Kolkata and Zorinpui by approximately 700 km3, substantially cutting logistics, transit time, and costs. This development has the potential to facilitate greater integration of the Northeast region and other regions of the country, as well as encourage India’s trade and strategic engagements with its Southeast Asian neighbours. With these prospects, the KMTTP can serve as one of the primary enablers of India’s Act East Policy.

This brief examines how interconnected regional instabilities and crises have undermined India’s connectivity objectives. It also identifies potential strategies through which India can protect and advance its strategic interests under these circumstances.

Challenges to the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project’s Completion

Originally scheduled to be completed in 2014, the KMTTP still remains incomplete, with its operational deadline now extended to 2027. While the project was launched to reduce India’s overdependence on the vulnerable Siliguri Corridor and secure an alternative route to the Bay of Bengal, this prolonged delay has constrained India’s broader connectivity agenda and the strategic importance of this multi-modal route.

One of the major challenges is the construction of the 110-km Paletwa-Zorinpui road link. The initial construction phases were hampered by the extremely rugged and hilly terrain between Paletwa and Zorinpui, increasing engineering complexity and cost4. These challenges continue to affect construction. Additionally, persistent security instability and conflict in Myanmar’s Rakhine and Chin States have disrupted supply chains, creating continuous operational security risks for project personnel5. Given the lack of stable governance in Myanmar, there are no credible assurances for long-term operational security of this vital land segment6.

Another challenge is the heightened political uncertainty in Bangladesh, with officials noting that political and administrative changes have caused delays in the development projects7. These intersecting crises threaten the reliability of India’s connectivity routes, interrupting trade flows, humanitarian access, and outreach to India’s eastern frontier, and as a result, limiting India’s regional influence and the integration of the Northeastern region.

Impact of Regional Volatility

Myanmar’s changing security landscape due to the ongoing civil war (since May 2021) has intensified India’s concerns regarding the KMTTP. Nearly 80 percent of the state is now under the control of the Arakan Army and the military junta has increasingly resorted to blockading trade routes and overland movement8. Although the maritime Kolkata-Sittwe route is functional and the inland waterway infrastructure is structurally complete, its sustained operation and technical requirements such as continuous dredging and navigation channel maintenance cannot be carried out safely and effectively due to fragmented control9.

10The influx of refugees from Myanmar has also created security, resource, and socio-political vulnerabilities for India, particularly in its Northeastern states. Reports suggest that this situation has led to an increase in transnational organised crime, including the smuggling of narcotics, arms and human trafficking. Mizoram, a key stakeholder in the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project, bears a disproportionate share of the resource burden. Yet it often struggles to provide essential aid, shelter and services like healthcare and education, which further strains its limited financial and infrastructural capacity. The lack of a national refugee protection framework in India further complicates the socio-political landscape of the entire region11.

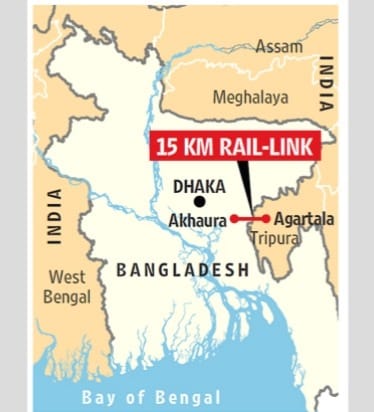

Furthermore, India’s bilateral relations with Bangladesh, which were originally the pillar of this project, have now entered a state of uncertainty and vulnerability. A decrease of 45 percent in rail trade year-on-year and a 20 percent decline in cargo movement in the financial year 2024-202512 highlight the growing complexities. Despite the inauguration of the Agartala–Akhaura rail line in November 2023, the line remains non-operational due to pending infrastructural work and may remain so in the future due to administrative delays. Furthermore, while India has secured operational access rights to a terminal at the Mongla Port in 2024, bureaucratic friction may hinder logistical functions13.

These challenges are compounded by the gradual expansion of Chinese presence in the Bay of Bengal, as China has been advancing the China–Myanmar economic corridor and the Kyaukphyu Sea port14. These projects are an integral part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and reflect the country’s broader energy security and geopolitical objectives, explicitly designed to mitigate the vulnerability inherited by the Malacca dilemma15. India’s limited success in securing its own logistical chains and reliable alternatives provides China with an opportunity to consolidate its influence through infrastructural and economic measures16, which may be unfavorable to Indian interests.

Also Read: India’s 2026 BRICS Presidency: Reinvigorating Multilateralism in a Fragmented World Order

Way Forward

Given that the Arakan Army controls major regions that are integral to the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project and is establishing local governance structures in those areas17, India may be forced to explore means of informal cooperation with the Arakan Army to secure functional stability18. However, since such engagement is politically sensitive, India has to ensure that the process aligns with its broader foreign policy principle of non-interference and respect for Myanmar’s sovereignty. India could also take steps to preserve and secure assets in the Bangladesh corridor, such as port access rights and the Agartala–Akhaura rail link, ensuring that they are operationally ready once the political situation turns favourable.

Additionally, India could consider the feasibility of embedding the KMTTP within BIMSTEC. This measure may not do much to change the domestic political challenges in Myanmar and Bangladesh but may promote transparency and strengthen India’s relations with the countries. India could put efforts into fast-tracking key regional agreements like the BIMSTEC Motor Vehicle Agreement and the Coastal Shipping Agreement, as they complement existing connectivity projects such as the KMTTP19.

Another viable option for India is to treat the India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway as an alternative for ASEAN outreach20. While the current progress on this project is uneven, in the long term, this highway could act as a gateway to all of Asia while also serving as a high-capacity counter-corridor to the China–Myanmar economic corridor. Through this approach India can strengthen its ability to protect existing assets and investments. It can also rely on multilateral partnerships to engage with Myanmar and Bangladesh and promote its connectivity projects. So, India could ensure its role as a reliable strategic anchor in the Bay of Bengal, transforming the Act East policy into a robust instrument of national and regional reliance, and become independent of immediate neighbours’ political volatility.

Conclusion

In light of the emerging challenges, it may be helpful for India to focus on preserving existing investments and assets through active diplomacy rather than territorial expansion. Sustaining even minimal operation of the Kolkata–Sittwe–Paletwa waterway could be beneficial for India, as it will reduce the burden on the Siliguri Corridor and potentially help boost the economy of the Northeastern states. This could help reposition the KMTTP from a geopolitical tool to a source of local revenue that fosters goodwill and reduces immediate physical risk.

India could also benefit from treating the Bangladesh route as a backup plan, ceasing further investments and expansions for the time being and utilising it fully only when political circumstances turn stable and predictable in Bangladesh. Moreover, India could leverage multilateral platforms to enhance bilateral relations with Myanmar and Bangladesh and secure connectivity routes. In all intents and purposes, the successful completion of the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project will be crucial for India’s long-term strategic credibility, economic reach, and regional stability, reaffirming its role in a more connected and resilient Indo-Pacific region.

Endnotes

- Gaens, Bart, Ville Sinkkonen, and Henri Vogt. 2023. “Connectivity and Order: An Analytical Framework.” East Asia 40: 209–228. ↩︎

- Singh, Mohinder Pal. 2025. “Siliguri Corridor: India’s Strategic Lifeline and a Growing Concern.” Times of India, May 29. ↩︎

- Sonowal, Sarbananda. 2025. “Kaladan project between India, Myanmar to be operational by 2027: Sononwal.” The Economic Times, July 7. ↩︎

- Seshadri, V. S. 2014. Transforming Connectivity Corridors between India and Myanmar into Development Corridors. New Delhi: Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS). ↩︎

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2024. Rakhine: A Famine in the Making. November 7. ↩︎

- Narasimha, ASL. 2025. “Kaladan Project to Be Operational by 2027: Sonowal.” Maritime Gateway, July 8. ↩︎

- Roy, Shubhajit. 2024. “India Says Its Development Projects in Bangladesh Have been Impacted.” The Indian Express, August 31. ↩︎

- Radio Free Asia. 2024. “After 2024 Setbacks, Junta Forces Now Control Less Than Half of Myanmar.” December 30. ↩︎

- Verma, Rahul, et al. 2025. “Appraisal of Geoenvironmental Threats Posed by Indo-Myanmar Kaladan Multi Modal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP) in Southern Mizoram, India.” Disaster Advances 18 (7): 61–67. ↩︎

- The Hindu. 2025. “Myanmar Refugees Threatening Security, Draining Resources: Mizoram Activist to Amit Shah.” The Hindu, March 12. ↩︎

- ACAPS. 2023. “India: Myanmar refugees – ACAPS.” Briefing Note, ACAPS, July 28, 2023. ↩︎

- Business Standard. 2025. “Rail, waterways trade between India and Bangladesh sees sharp contraction in FY25”. Business Standard, June 2. ↩︎

- Banerjee, Sreeparna and Chakraborty, Debashis. 2025. “Facilitating India-Myanmar Trade through Sittwe Port: Opportunities and Challenges.” ORF Occasional Paper No. 463, February 4. ↩︎

- Hussain, Mehmood. 2021. “CPEC and Geo-Security behind Geo-Economics: China’s Master Stroke to Counter Terrorism and Energy Security Dilemma.” East Asia. ↩︎

- Myers, Lucas. 2023. “China’s Economic Security Challenge: Difficulties Overcoming the Malacca Dilemma.” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, March 22. ↩︎

- Choudhary, Mohit. 2023. “China’s Malacca Bluff: Examining China’s Indian Ocean Strategy and Future Security Architecture of the Region.” Air University (AU), February 6. ↩︎

- Martin, Michael. 2025. “Arakan Army Posed to ‘Liberate’ Myanmar’s Rakhine State.” CSIS.org. ↩︎

- Chatterjee, Bipul. 2023. “The Arakan Army and Its Impact on India: Rising Tensions Along The Eastern Frontier.” CLAWS. ↩︎

- Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSETC). n.d. Connectivity. ↩︎

- Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA). The India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway and Its Possible Eastward Extension to Lao PDR, Cambodia, and Viet Nam: Challenges and Opportunities, Integrative Report. Jakarta: ERIA ↩︎